February 2022 – FED ACCOUNTING WITHIN QT, find whole research here

| We have received questions recently about possible losses for the Fed if it chose to sell assets. We start with a basic accounting, proceed to realized and unrealized losses the Fed could sustain, and then where such losses could lead. |

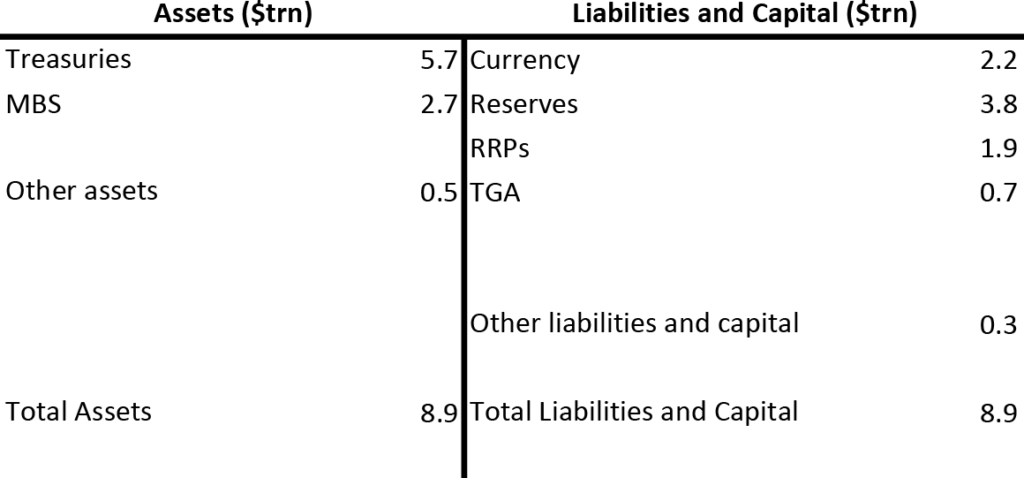

| Like any balance sheet, the Fed has assets, liabilities, and capital. Total assets are currently about $8.9trn, comprising $5.7trn in Treasury securities, $2.7trn in mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and $0.5trn in other assets. The Treasuries and MBS are the primary interest-bearing assets and have an average coupon of about 2.3%. On the liability side of the balance sheet, there is $1.9trn in reverse repos (RRP), $3.8trn in reserve balances of banks, which are interest-bearing at the rates set by the Fed. In addition, $2.2trn in currency, roughly $0.7trn in the Treasury’s general account (TGA), which are zero-interest liabilities, and about $0.3trn of other liabilities and capital. Some simple arithmetic allows us to get a ballpark estimate of the “breakeven rate” for the federal funds rate, that is the level where interest expense reaches interest income and the Fed’s net income is wiped out. Currency and the TGA jointly are roughly 1/3 of the liabilities, which implies that the average interest expense across all liabilities is only 2/3 the rate paid on reserves and RRPs. If we roughly approximate those rates by fed funds, when the federal funds rate is 3/2 times the average coupon on assets, net income will be zero. The Fed’s current average coupon is 2.3%, so the breakeven rate is about 3.5%. At rates below this breakeven, the Fed is earning profits, which, after accounting for operating costs, are remitted to the Treasury. For reference, in 3Q2021, the Fed remitted $31bn to the Treasury, reducing the Treasury’s need to borrow. Can the Fed make losses, and would losses put the Fed into negative equity? The answers are “yes” to the first question and “no” to the second. In Federal Reserve accounting, assets are booked at amortized cost and are not marked to market. On the H.4.1 statistical release there is a line item for the face value of the securities and a separate line item for the unamortized premiums and discounts. The Fed publishes quarterly income statements with estimated unrealized mark-to-market valuation of the System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio, but the Fed does not recognize losses on its income statement unless the losses are realized. Selling assets could lead to realized (and recognized) losses, but premiums and discounts are straight-line amortized, so at maturity, there is neither loss nor gain. There are two clear scenarios where the Fed may have an operating loss. If the Fed were to raise the funds rate above the breakeven rate, net income is negative. But over time, as the Fed begins to reduce its balance sheet—whether by sales or by passive runoff—the breakeven level of the funds rate rises. When the balance sheet begins to run off, Treasuries and MBS holdings will fall. On the liability side, either reserves or RRPs will fall to keep the balance sheet in balance. Moreover, over time, currency tends to grow, further reducing reserves. So, over time, the interest-bearing liabilities will fall as a share of the balance sheet. With an average coupon of 2.3%, if interest bearing liabilities fall to be 1/2 of the balance sheet, the breakeven rate will rise to 4.6%. The more the balance sheet shrinks, the higher the breakeven federal funds rate. If the Fed were to sell securities at a loss, the loss would be reflected in the income statement, reducing net income, and therefore the remittance to the Treasury. Possible sales of MBS are currently being discussed. As noted in this piece, the most recent estimate of unrealized mark-to-market losses on the MBS portfolio is about $100bn. Of course, selling the entire portfolio would likely increase the realized loss by lowering market prices. But as noted above, remittances are strong, at times reaching $100bn in a single year. So allowing some passive runoff and spreading the rest of the loss over a few years would likely not completely wipe out net earnings. The specific execution would determine the outcome. Of course, in some scenarios, rates could rise dramatically more than expected, with either the funds rate above the breakeven rate or sufficiently large realized losses that net income is wiped out. Could the Fed go bankrupt? The answer is “no.” Under Federal Reserve accounting rules, if income turns negative, capital is not impaired. Instead, remittances to Treasury would cease, and based on the logic that the Fed has a 100% marginal tax rate, negative income in a reporting period gets booked and accumulated as a “deferred credit asset” on the Fed balance sheet. Essentially, the Fed can carry forward the losses to a future period when earnings are positive. Over time, the balance sheet would continue to shrink, and net income would become positive again. At that point, the Fed would not begin to remit to Treasury, but rather would retain excess earnings against the deferred credit asset. After past losses are recouped, remittances to Treasury would begin again. Whereas some central banks have a process for explicit recapitalization, in essence for the Fed there would be future retained earnings. |

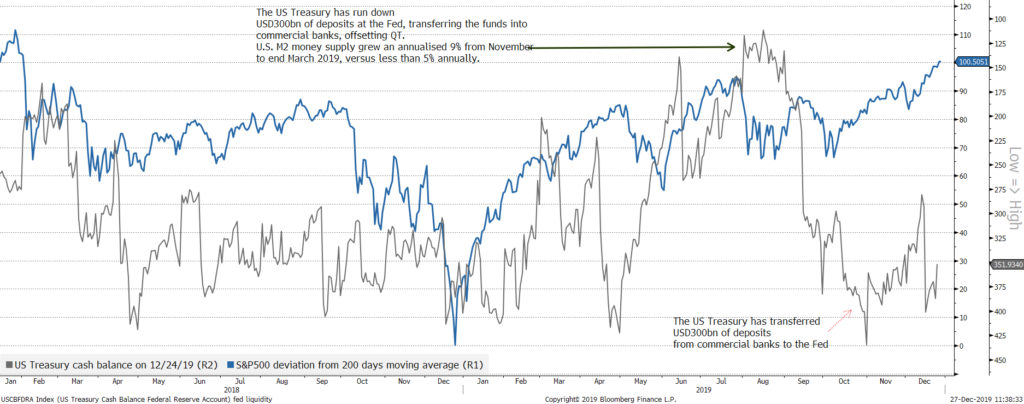

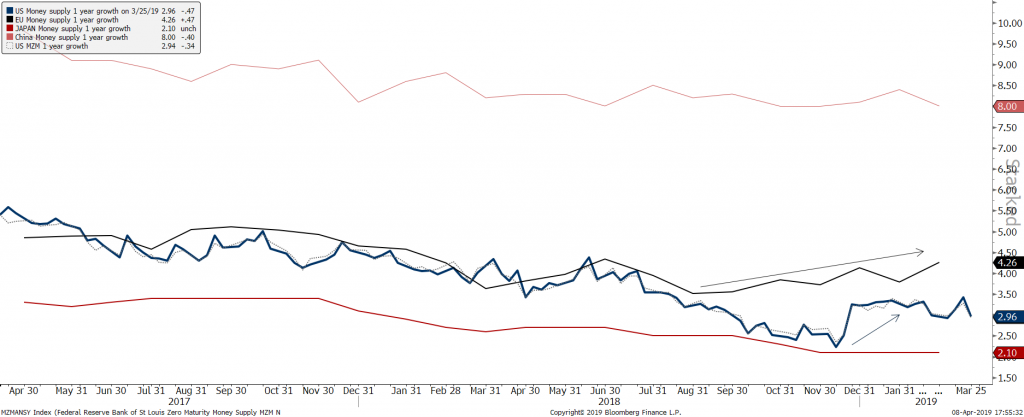

Liquidity has strongly increased in November as the Treasury has run down USD 150bn of deposits at the Fed, transferring the funds into commercial banks. US M2 Money supply grew an annualized 9% since november, versus the usual annualized 5%.