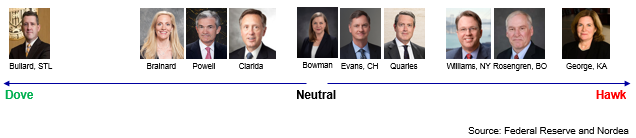

July 2019: https://e-markets.nordea.com/#!/article/49987/fed-watch-warming-up-for-a-july-cut from nordea bank – The minutes of the June meeting revealed that the FOMC participants generally agreed that downside risks to the outlook for economic activity had risen materially since their May meeting – particularly those associated with ongoing trade negotiations and slowing economic growth abroad. Consequently, nearly all FOMC members had revised down their assessment of the appropriate path of the federal funds rate, with “a couple of members” even favouring a cut at the June meeting. Arch-dove James Bullard had already been confirmed as a dissenter at the meeting, while we suspect the 2019-non-voter Kashkari to be the other one.

Overall, seven (of 17) FOMC participants believed two rate cuts would be appropriate this year while one participant opted for one rate cut. Therefore, it will only take one participant to move the median to a rate cut already this year.

May 02nd: Fed policy outlook: this has got to be NIRVANA for the Fed Fed policy outlook: this has got to be NIRVANA for the Fed, a solid economy, muted inflation, and rising productivity. Hence there is no urgency for the FOMC to act one way or another. This report and other recent data fully reinforce Powell’s comments where he said “I see us on a good path for this year,” with him and other officials noting the “good spot” the economy is in. The futures are still priced for a rate cut as the next action, but that’s being pushed further into the future, beyond Q1 2020. Just after the FOMC headline statement on Wednesday, a 25 bp easing was priced in for Q4.

Read more at:

https://thefly.com/landingPageNews.php?id=2903157

March 20 – FOMC decision in aggregate was more dovish than expected (and the attendant market moves were textbook: Treasuries rallied/yields fell, the USD fell, USD-sensitive groups like energy outperformed, and financials puked). In particular, the dots were knocked down by more than expected in aggregate (from two to zero in ’19 and nearly to zero for ’20) while the core PCE forecasts stayed unchanged (the combination of this, a more dovish policy path and static inflation forecasts, is an important sign of support for the shift to an average inflation target and this may wind up being the key takeaway from the Wed FOMC decision; the Fed’s June 4-5 conf. in Chicago is the next critical event for this targeting shift). The written statement was largely as expected and the balance sheet plan too mostly aligned with the consensus (Powell’s tone around growth during the presser was a bit more sanguine than the statement tone).TTN Analysis: Comparative analysis of current vs JAN FOMC statements: Notes inflation has declined due to energy; Notes weak Feb payrolls data, through recent avg remains strong; Notes slower spending and business investment in Q1 ** Revisions bolded: Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in January indicates that the labor market remains strong but that growth of economic activity has slowed from its solid rate in the fourth quarter [revised from “Job gains have been strong, on average, in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low”]. Payroll employment was little changed in February, but job gains have been solid [revised from “strong”], on average, in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Recent indicators point to slower growth of household spending and business fixed investment in the first quarter [Revised from “Household spending has continued to grow strongly, while growth of business fixed investment has moderated”]. On a 12-month basis, overall inflation has declined, largely as a result of lower energy prices; inflation for items other than food and energy remains near 2 percent. On balance, market-based measures of inflation compensation have remained low in recent months, and survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed. Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. In support of these goals, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 percent. The Committee continues to view sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective as the most likely outcomes. In light of global economic and financial developments and muted inflation pressures, the Committee will be patient as it determines what future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate may be appropriate to support these outcomes. In determining the timing and size of future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess realized and expected economic conditions relative to its maximum employment objective and its symmetric 2 percent inflation objective. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Jerome H. Powell, Chairman; John C. Williams, Vice Chairman; Michelle W. Bowman; Lael Brainard; James Bullard; Richard H. Clarida; Charles L. Evans; Esther L. George; Randal K. Quarles; and Eric S. Rosengren.– Source TradeTheNews.com

Fed officials (esp. Williams) have been hinting at a shift in the inflation targeting framework for months and on Fri this broke into the fore as not only Williams but Clarida too suggested policy could eventually evolve such that the aim becomes to achieve a 2% average inflation level over the course of a cycle (vs. a 2% discrete goal). The implication of changing from discrete to average means the Fed will ostensibly permit inflation to run above 2% to compensate for the time it’s tracked below that level. Such a change would obviously be extremely dovish in theory but the SPX should curb its enthusiasm for now: 1) the Fed is simply undergoing an analysis at the moment and won’t make a final determination until the first half of 2020 (although a big conf. coming up in Chicago this June 4-5 could provide additional details); 2) the Fed’s proposal may prove to be quite controversial and could invite political scrutiny from members of Congress (esp. as the inflation change, to the extent it happens at all, would occur only a few months before the 2020 presidential election); Powell’s testimony this week (2/26 and 2/27) will allow members of Congress to ask questions about the inflation change; 3) the new inflation language would probably be emphasized only when policy reaches the zero-bound again (i.e. the Fed Funds rate returns to zero), something that won’t happen unless the US economy is in recession (and a recession would be much worse for stocks than a >2% inflation target would be positive); 4) non-equity asset classes aren’t necessarily reacting in way one would expect if the Fed were about to radically change its inflation framework (gold prices are well off their lows but have hit the ~$1350 level on several occasions over the last several years, the DXY remains well bid whereas it should be weakening, the TSY curve isn’t steepening as one would expect, and 10yr inflation expectations aren’t even back to where they were in June-Sept).

- This week’s Fed decision will be remembered for a while, because it’s only the fifth time in 50 years that the Fed has undertaken a mid-cycle pause and because the Committee so quickly reversed all aspects of its messaging from the December meeting. The statement revived the word “patient” from the Yellen era, dropped references to further tightening and included an addendum confirming flexibility on balance sheet policy. (We expected the first change but neither the second nor third). The press conference, which in the past had ranged

- Whether the Fed is truly changing how it views its policy objectives – to become more a risk manager (Bernanke and Yellen blinked similarly), protector of the stock market (like Greenspan), or generator of inflation (core PCE has rarely exceeded 2% in the past 20 years) – won’t be known for some time unless Chair Powell undertakes Kuroda-style announcements. During this finding-out phase, markets must contend with a complicated problem of how to assess value when the Fed’s short-term path is clear, its medium-term path hazy and therefore the longevity of this (almost) oldest US expansion quite uncertain. The simple, tactical perspective for the next several weeks is that mid-cycle Fed pauses have always boosted risky market meaningfully, so almost anything should beat Cash and US dollars. The more nuanced view for the next few months recognizes that factors beyond the Fed have weighed on global growth, so the upside on cyclical assets should be constrained without other policy catalysts. The tougher asset allocation call for the next few years is whether Fed policy is prolonging both the economy’s expansion and preserving the corporate sector’s wide margins.

- For the next several weeks, we still think the Fed pause playbook outlined before the FOMC meeting presents a reasonable baseline. The view pre-FOMC was that bond markets had priced the majority of the yield decline typically associated with Fed pauses, but that other asset classes had not front-loaded such moves. On average over the four previous Fed pauses/policy reversals in 1967, 1987, 1995 and 2016, US HG Credit tightened about 30bp, the S&P500 rallied about 10%, the trade-weighted dollar declined about 4% and Gold rallied 3%. The resulting price momentum generated by the Fed shift also tended to improve hedge fund alpha generation.

Our Key Takeaways:

- The Fed’s first meeting of 2019 proved to be an eventful one, with the FOMC delivering a meaningfully dovish statement while at the same time taking a step towards an early end to balance sheet normalization.

- Key changes in the FOMC statement came in the Committee’s guidance on the policy outlook and assessment of risks to the outlook. The FOMC is now “patient,” and no longer has a strong bias on whether the next rate move will be up or down.

- As if the dovish statement and cautious policy outlook weren’t enough, Fed policymakers also delivered an update on balance sheet normalization at the January meeting that showed the FOMC is moving closer to an early end to balance sheet rundow

The 2pmET formal FOMC statement was very surprising on a number of fronts, including changing “further gradual increases” to “future adjustments” (signaling the next move could be a hike or a cut) while promising to be “patient” before adjusting policy incrementally given “global economic and financial developments and muted inflation pressures”. Meanwhile, a second statement hit at 2pmET in which the Fed promised to keep an “ample supply of reserves” in the system while pledging to adjust the run-off pace should conditions warrant (“the Committee is prepared to adjust any of the details for completing balance sheet normalization in light of economic and financial developments”). During the press conf., Powell acknowledged int’l growth pressures but he said the Fed’s broad outlook on growth hasn’t shifted dramatically (he did say though that the case for rate hikes has weakened somewhat, more b/c of muted inflation rather than dramatically softening growth). Powell said balance sheet normalization will complete sooner, and leave the balance sheet larger, than was thought previously (he said the Fed will be finalizing balance sheet plans at upcoming meetings). On rates, Powell indicated the present FF is within the range of neutral. He noted how financial conditions tightened significantly in Q4 and remain tight presently and noted this something the Fed has to take into consideration. Note that the minutes from this meeting, which will be super important, are due out Wed Feb 20.

TTN Analysis: Comparative analysis of current vs Dec FOMC statements: REMOVES reference to further rate hikes; REMOVES “roughly balanced” risks clause; Economic activity seeing solid growth (vs ‘strong’); inflation measures have slipped recently Revisions bolded: Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in December indicates that the labor market has continued to strengthen and that economic activity has been rising at a solid rate [revised from “strong rate”]. Job gains have been strong, on average, in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Household spending has continued to grow strongly, while growth of business fixed investment has moderated from its rapid pace earlier last year. On a 12-month basis, both overall inflation and inflation for items other than food and energy remain near 2 percent. Although market-based measures of inflation compensation have moved lower in recent months [new clause], survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed. Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. [DELETES gradual hikes clause: “The Committee judges that some further gradual increases in the target range for the federal funds rate will be consistent with sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective over the medium term.”] In support of these goals, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 percent. The Committee continues to view sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective as the most likely outcomes [revised from “In view of realized and expected labor market conditions and inflation”]. In light of global economic and financial developments and muted inflation pressures, the Committee will be patient as it determines what future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate may be appropriate to support these outcomes [Revised from “The Committee judges that risks to the economic outlook are roughly balanced, but will continue to monitor global economic and financial developments and assess their implications for the economic outlook.”] In determining the timing and size of future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess realized and expected economic conditions relative to its maximum employment objective and its symmetric 2 percent inflation objective. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Jerome H. Powell, Chairman; John C. Williams, Vice Chairman; Michelle W. Bowman; Lael Brainard; James Bullard; Richard H. Clarida; Charles L. Evans; Esther L. George; Randal K. Quarles; and Eric S. Rosengren.–

The problem for analysts and investors is there was no prece-dent for the effort and no one’s certain about the ramifications of removing it. Former Fed Chair-man Ben Bernanke once said the problem with quantitative easing is “it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory.”

It’s worth emphasizing how portfolio rebalancing works in conjunction with interest rate levels to move markets. With quantitative easing (QE), the Fed removed assets of long duration (Treasuries and agency MBS) and replaced them with assets of zero duration (cash). This occurred just as the incentive to own longer-duration assets of all kinds – e.g., corporate debt and equities – was rising, thanks to near-zero yields on shorter-duration assets. As a result, portfolios rebalanced toward scarce, riskier assets of longer duration, which drove prices higher. With balance sheet normalization, or quantitative tightening (QT), the Fed is removing assets of zero duration and, indirectly, replacing them with assets of longer duration. If the policy rate were still near zero, the relative demand for longer-duration assets might remain robust, even in the face of higher supply. However, the Fed is implementing QT with a much higher policy rate (see Exhibit), leading to higher demand for shorter-duration assets. As a result, portfolios are rebalancing away from riskier assets of longer duration, and this is now driving prices lower. This framework suggests that the Fed’s decision to exercise more patience in raising rates further should prevent accelerated de-risking for now. At the same time, the previous incentives to de-risk still exist, and the Fed continues to force portfolio rebalancing.

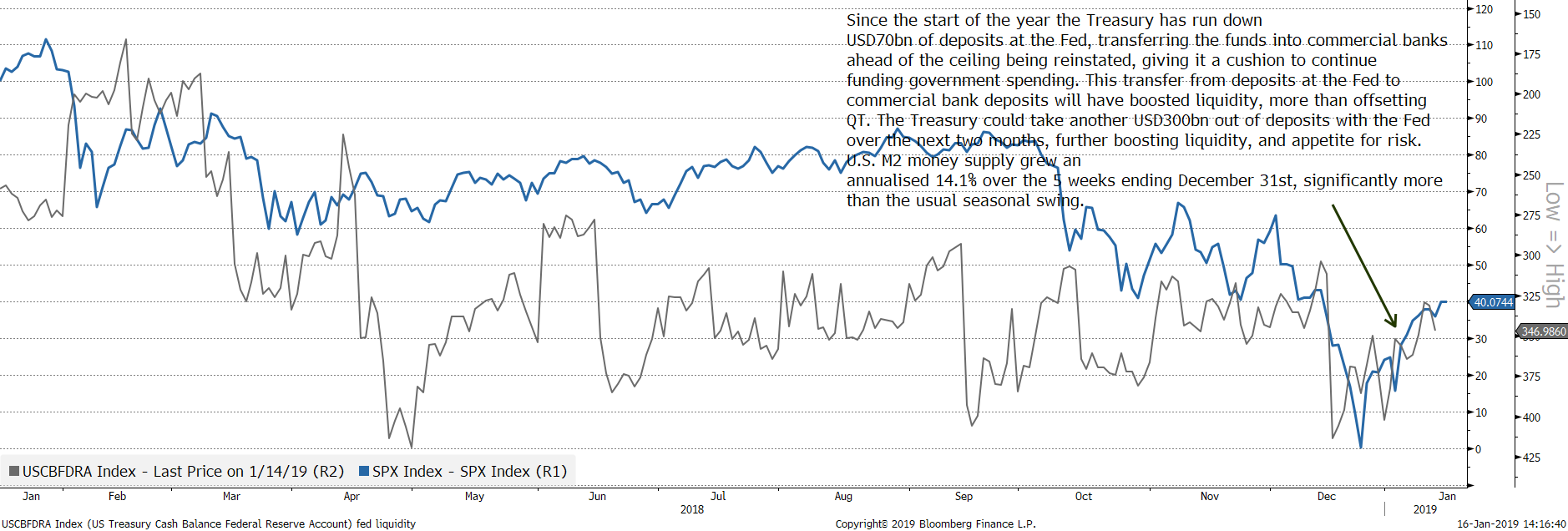

Since the start of the year the Treasury has run down

USD70bn of deposits at the Fed, transferring the funds into commercial banks

ahead of the ceiling being reinstated, giving it a cushion to continue

funding government spending. This transfer from deposits at the Fed to

commercial bank deposits will have boosted liquidity, more than offsetting

QT. The Treasury could take another USD300bn out of deposits with the Fed

over the next two months, further boosting liquidity, and appetite for risk.

Whether in anticipation of this or otherwise, U.S. M2 money supply grew an

annualised 14.1% over the 5 weeks ending December 31st, significantly more

than the usual seasonal swing.

he US debt ceiling is back as a major tactical driver of markets, just like it was from 2015 through 2017, but not in the way that many investors assume. The US debt ceiling suspension, signed in February 2018, expires at the beginning of March this year. The Treasury must carry out special measures if it expects a delay raising the debt ceiling in March, and a delay looks highly likely. Under special measures the Treasury must draw down its deposits at the Fed and deposit the cash in various government departments’ accounts at commercial banks, for future use to pay government salaries and contractors’ fees.

When the Treasury deposit is with the Fed, it is inert. The Fed does not lend out the Treasury’s deposit either to the economy or to money markets. But when the funds are transferred to government departments’ commercial bank accounts, this raises commercial bank deposit liabilities, which increases the money supply. And the commercial banks either lend those deposits to the economy or into money markets. Consequently, Treasury deposit withdrawals act like QE, and Treasury deposit build-ups act like QT. Over certain discrete periods, the size of the moves can be so large, that they become the dominant driver of markets. When Treasury deposits come down quickly, it is bullish for risk assets, bullish for gold and bearish for the dollar.

The Treasury has withdrawn US$56bn since January 1st and I anticipate that the it will withdraw another US$300-320bn over the next eight weeks, the equivalent to running QE at a US$2trn annual pace over the period, enough to overwhelm current QT. Once the debt ceiling is raised/suspended, likely in Q2, deposits will rise, and once again drain liquidity from the system. When combined with QT that will likely cause an aggressive risk off event.

The key message; the liquidity and risk picture is benign for now, but beware the ides of (late) March!

January 9th: Fomc minutes

The minutes of the December FOMC meeting affirmed the message received in public comments from policymakers over the past week that, “especially in an environment of muted inflation pressures, the Committee could afford to be patient about further policy firming.” The minutes also explained the Committees decision to modify the forward guidance language referring to the Committee’s expectation for “further gradual increases” in the fed funds rate by replacing “expects” with “judges” in order to better convey their commitment to data dependency. Though the decision to raise rates in December was unanimous, the minutes showed that “a few” participants favored no change, as they judged that the lack of inflationary pressures “. Moreover, the minutes highlighted a range of downside risks that participants would be monitoring, including concerns around a slowdown in global economic growth, a more rapid waning of fiscal stimulus, trade policy developments, a further tightening of financial conditions, and greater-than-expected negative impacts from monetary policy tightening.

January 4th: Fed Chief Walks Back ‘Autopilot’ Remark

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell took a mulligan on Friday, offering a much more dovish and flexible Fed policy outlook than he did after the Dec. 19 rate hike. Powell said that quantitative tightening won’t remain on autopilot.

When asked if he would resign at the request of President Trump, who has been criticizing the Fed chief and even reportedly asked about firing him, Powell also said no.

Powell spoke after the December jobs report blew away Wall Street estimates with a gain of 312,000 jobs and 3.2% wage growth. The jobs data gave support to Powell’s confidence in the economic outlook, a day after the ISM manufacturing index saw its sharpest fall since 2008.

But Powell said that the financial markets are sending “conflicting signals.” He said the Fed is ready “to adjust policy quickly and flexibly and to use all of our tools,” including its balance sheet.

While Powell said that the Fed is now listening carefully to markets, he doesn’t necessarily agree with the criticism of the Fed’s balance-sheet wind-down. Still, he said the Fed will continue to examine how markets are responding to it, adding that the central bank wouldn’t hesitate to change course if the balance sheet policy was becoming a problem.

Because Powell isn’t ready to throw in the towel on Fed rate hikes this year, an early phase-down of quantitative tightening is the most logical step to combat uncertainty over global growth and trade friction. There’s not much Powell can do to ease investor concern about rate hikes. That’s because, even after the bodacious jobs numbers, markets were pricing in only about a 2% chance of a rate hike in 2019.

Powell arguably punched the ticket for the sagging S&P 500’s trip into bear market territory on Dec. 19. That’s when the Fed stubbornly stuck to script, raising rates for the fourth time in 2018. Powell added insult to injury with his post-meeting press conference, stating that the Fed’s unloading of Treasuries and mortgage securities would continue on “autopilot.”

Those assets were bought via quantitative easing to help the economy recover from the financial crisis. The idea was to hold down interest rates and encourage investors to take on risk.

At present, the Fed is unloading up to $50 billion in assets per month as the securities reach maturity. To some extent, this quantitative tightening encourages investors to put money into risk-free government securities, rather than riskier stocks and bonds. Market strategists blamed Powell’s Dec. 19 comment that the balance-sheet unwind was on “autopilot” for the post-meeting stock sell-off.

While it’s unclear how negative those purchases are, the Fed appears to be aligned against the stock market as economic growth cools and stocks hit bear market territory.

December 20th: Stocks Tumble on Deepening Fears of a Fed Mistake – Even though the Fed signaled a less aggressive rate path, markets had been looking for signals it might be done raising rates, which Mr. Powell didn’t offer. He also said the Fed was committed to steadily letting its crisis-era holdings of Treasury and mortgage bonds run off as planned, following a strategy initiated last year. Mr. Powell repeatedly said political pressure would never influence the Fed’s decisions. “Political considerations have played no role whatsoever in our discussions or decisions,” he said. “Nothing will deter us from doing what we think is the right thing to do.” The updated projections released Wednesday showed 11 of 17 officials expected they would need to raise rates no more than two times next year, compared with seven of 16 officials who held that view in September. The changes signal the impending close of a three-year chapter of policy “normalization” in which officials lifted interest rates slowly after holding them near zero for seven years to nurse an economy battered by the 2008 fin crisis. Now, they think they need to raise rates a bit more to prevent solid U.S. economic growth from fueling excessive inflation or asset bubbles, but they aren’t sure how much further to go or how quickly. Their decisions on how to manage this new phase of fine-tuning their policy will depend largely on near-term changes in the economy and financial markets. “Markets either have a much different Federal Reserve reaction function in mind, or they have a series of extraordinary shocks they believe are going to hit the economy in 2019, which is a different place from where the Fed is,” said Mr. Sheets, adding that investors anticipate fewer rate increases next year than the central bank. Mr. Powell could have positioned the Fed for the possibility the markets are right and the data are about to take a turn for the worse with a much more ambivalent statement about future rate increases. The fact he didn’t is risky—for the economy and him, personally, since President Trump will likely hold him responsible for a recession. Markets and economic data frequently diverge; the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions, the old joke goes. But that is actually a pretty good record; the Fed hasn’t predicted any of them. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell added to investors’ jitters when he said the Fed was committed to letting its holdings of bonds run off as planned, despite some market participants’ concerns that the process was fanning volatility.

December 18th: President Donald Trump criticised the Federal Reserve for its current series of interest-rate increases, days before the US central bank is expected to push up interest rates again. “It is incredible that with a very strong dollar and virtually no inflation, the outside world blowing up around us, Paris is burning and China way down, the Fed is even considering yet another interest rate hike. Take the Victory!” Trump wrote in a tweet.

December 7: change in Fed officials’ rhetoric. In particular, the central bank’s chairman, Jerome Powell, last week said the fed-funds rate was close to neutral, the elusive and unobservable level that neither spurs nor slows the economy, a view echoed by other Fed speakers since then. That was a shift from early October, when he opined that the neutral rate was a ways off and the Fed may want to go beyond there, comments that pushed up longer-term Treasury yields and roiled the stock market.

November 29: The longer-run dots in the SEP indicate FOMC participants’ estimate of neutral. The latest range of those estimates is from 2.5% to 3.5%. The current 2.2% funds rate is reasonably described as “just below” that range. The median and modal estimate of the range is 3.0%; at the pace of hike a quarter it would be fair to describe the current funds rate as a long way from that point, probably. Powell almost certainly knew that the tone shift would be welcome by risky assets, but ultimately nothing he said boxes in the Committee’s decisions.The two key dovish quotations were: 1. “Interest rates are still low by historical standards, and they remain just below the broad range of estimates of the level that would be neutral for the economy that is, neither speeding up nor slowing down growth.” 2. “We also know that the economic effects of our gradual rate increases are uncertain, and may take a year or more to be fully realized.” The first quotation walks back Powell’s ‘far below neutral’ off-the-cuff comment from October 3rd. The focus on a range of possible values for neutral is dovish and aligns Powell with the approach taken by Vice Chair Clarida in his speech yesterday, which put the range at 2.5-3.5%. The second quotation is also dovish, arguing for a slow approach to policy normalization because it takes considerable time to assess the effects of past tightening..

Trump called on the Fed to cut interest rates despite signs that another hike is on the way as soon as next month. And one of Jay Powell’s colleagues seems to agree. Minneapolis chief Neel Kashkari said the central bank should pause its tightening cycle, adding that regarding Trump: “Substantively, we’re probably saying something similar, though I would argue our styles are somewhat different.”

Nov 16th: As finally the Fed reacts: Two regional Fed bank presidents cited cooling activity abroad as they urged caution in raising interest rates. Atlanta Fed’s Raphael Bostic, who votes, said ignoring weaker growth abroad is a “recipe for a policy mistake” and said policy isn’t “too far” from neutral. Minneapolis Fed’s Neel Kashkari said it’s hard to know if slower growth abroad is only temporary. 5 hours after, they counter: {us} Fed rhetoric a headwind – vice chair Clarida spoke on CNBC this morning and (like Powell) he doesn’t sound as nervous about the economy as stocks seem to be (his sanguine tone will likely be considered a neg. as markets are increasingly worried that growth is slowing beyond Fed expectations). Clarida (and Powell earlier in the week) both acknowledged some int’l slowing but neither thinks this is creating enormous headwinds for the US (for now). The next major Fed speech will likely be Powell’s address to the NY Economic Club on 11/28 (Powell also will be testifying before Congress on 12/5).

November 15, 2018, “we are in a good place now and I think our economy can grow, and grow faster.” Chair Powell

“over time folks will get used to the idea that we can and will move at any meeting.”

On the recent slowdown in housing indicators the Chair did not appear to be overly concerned citing that material costs, labor scarcity, and higher mortgage rates are all working together to create a softening environment.

On the recent stock market volatility Chair Powell stressed that the Fed looks mainly at the real economy, but “financial conditions and financial market activity matter a lot for that.” He acknowledged that when equity prices go down or are volatile there tends to be an effect on the economy. But he stressed that it is “one of many, many factors that go into a very large economy.”

On emerging markets Chair Powell cited decelerating (though still healthy) global growth, a strong dollar, and trade uncertainty as creating headwinds. Moreover, “our economy is woven tightly into global supply chains so growth abroad matters.” This year has seen “a bit of a slowdown….that is…chipping away at growth…that is concerning so we are monitoring it”. Though he reminded us that the Fed’s mandate concerns only U.S. conditions, what happens around the world is “really important… half of which is driven by emerging market countries.”

Finally, when asked about the Fed’s current program of balance sheet runoff, Chair Powell said the plan to normalize the balance sheet is going “very well.” The Fed is returning it to a normal size, but “we don’t know what the equilibrium is in the longer-run”. [] He stressed that of course will depend on the demand for currency and reserves. One thing is clear and that is the Fed is in a process to shrink its balance sheet and they “are on track to do that.”